The most uninteresting guests on business television

No question, Bill Gates is the most uninteresting, lousy, useless guest on television.

There's nothing he wants to say, aside from "technology is the future." He doesn't want to offend or antagonize anyone and somehow risk the charmed life he and generations of descendants will lead.

Sure, there are other contenders … Mohamed El-Erian will identify 3 reasons why something might happen and 4 why something else might not happen. Michael Burns will tell you how great the next Jennifer Lawrence movie is. Marc Faber will insist that the crash is really just around the corner.

Of course, these are fine chaps. If ever unguarded, they undoubtedly have interesting things to say. But that's never gonna happen.

Bookers on business and PBS outfits (that would be Charlie Rose) should drop these contacts from the Rolodex.

One fellow though who has entered this rare space is exchange entrepreneur Brad Katsuyama, who has the kind of message television loves (people are getting fleeced in the stock market by HFT) but actually nothing to say.

On Friday, Nov. 25, 2016, Katsuyama turned up again on "Wall Street Week," insisting that for "the everyday person," IEX "first and foremost prioritizes their interests."

But then he says, "If you're gonna go buy a hundred shares of Microsoft through an online broker, go for it. Right, the market can suit you. Uh, but if you're invested in a mutual fund, and they're trying to buy a million shares of Microsoft, it's a very different situation and game for them."

So on the one hand, IEX is for the little guy; on the other, it only matters for the folks making $60 million MSFT investments.

We don't know anything about physics — or really anything about anything for that matter — but we find it hard to believe an exchange can ensure that every participant becomes aware of the information at precisely the same time.

Katsuyama has never explained this nor how his exchange cures whatever ails the everyday investor (see further down this page).

Meanwhile, Charles Gasparino rightly observed on this episode that Donald Trump is trying to sell a "boondoggle infrastructure project to Congress." Gasparino declared Trump a "big tax-and-spend guy."

No doubt. Thankfully Trump has expressed disdain for military engagements, but once all the treats and goodies are handed out, this still figures to be a bigger expansion of government than even what occurred under George Bush.

Shockingly, Melissa Francis said with a straight face that this is "the opposite of a boondoggle."

Equally shockingly, Liz Claman claimed that Trump "could eyeball any bridge contract and say, 'Wait a minute, there's redundancy here.'"

This page won't opine on whether Claman or Francis was more scorching. #tooclosetocall

On the same program, Larry Pitkowski of Goodhaven said he wants to buy companies that are cheap and likes WTM and WPX.

Great moments in presidential interaction: George Bush says the president ‘generally doesn’t run into anybody’

It wasn't until well into the program, but the Oct. 14, 2016, episode of "Wall Street Week" produced some interesting assessments of Hillary Clinton's relationship with Wall Street and the media in general.

It should be noted there were references to content of stolen emails, something this page will generally not report.

Anyway, aside from the panelists essentially declaring Elizabeth Warren the most powerful person on the planet when she's accomplished … what exactly … besides griping at CEOs in committee hearings … Gary Kaminsky contended that complaints about Clinton siding with Wall Street are off the mark. "The public is being led to believe that these speeches are all cozy and warm … She doesn't wanna be there. She doesn't like the people. She wants the money," Kaminsky explained.

Nevertheless, Charles Gasparino said Lloyd Blankfein is "very close" to Clinton.

Anthony Scaramucci said the only reason Clinton didn't speak at the SALT Conference "is that she wanted to be there for 59 minutes and 59 seconds." We're guessing that means that her camp insisted on staying less than an hour and indicated she wouldn't be attending any private dinners or undergoing any (gasp) regular, remotely-near-the-radar everyday conversation.

(See, that brings to mind when Larry King asked W., "Do you run into people who say, 'I don't know.' Or do you run into mostly people who say, 'I support you'?" And W. responded, "I run into both. And when you say 'run in,' the president generally doesn't run into anybody. I mean, we're driving…")

The Clintons are obviously the nation's preeminent political players and have been for a generation. They know all the angles. They certainly derive more enjoyment out of playing the game than any sort of governmental accomplishment. They haven't "run into" an average American in decades. Their chapped brand of politics is far beyond Chap-Stick-able. You couldn't buy a real conversation with these people if you had all the money of all the guests of "Wall Street Week."

The debates are virtually meaningless in affecting people's votes, but what never gets mentioned in the post-debate analysis is that Americans are watching this woman for 90 minutes and realizing, "omg, we've gotta pay attention to this person for 4 more years??!!!????"

The Clintons returning to the White House is going to be like Joe Gibbs returning to the Redskins.

During its Fox Business run, "Wall Street Week" too often looks like one of the channel's regular shows and lacks the unique appeal of the Louis Rukeyser version. While it boasts many fine and respected guests, most are private people who likely cringe at the prospect of making waves and instead immerse themselves in oceans of generalities. To paraphrase John Edwards, it's 2 programs, one with cautious business predictions and the other with Gasparino's punch. With virtually no data or ticker or scroll, visually the program looks too much like an '80s CNN startup. When politics fade temporarily in the rear-view mirror, the show's going to need some muscle besides Gasparino's biceps.

Trump to appear July 15

on ‘Wall Street Week’

At the end of the July 8 "Wall Street Week" — in which Greg Fleming spoke freely with his hands — host Anthony Scaramucci announced that Donald Trump will be the show's guest July 15, certainly one of the biggest gets in the franchise's history, including the days of Louis Rukeyser.

Skeptics may note that this might not exactly be a Dan Rather-esque interview — Scaramucci is a member of Trump's finance committee and is "on the airplane with him" (according to Gasparino) — and that presidential-candidate scheduling is subject to the whims of the day (meaning there's always the chance it won't happen).

But assuming it does, this event could produce a lot of quotable material and perhaps some feisty debate depending on who's part of the panel. On July 1, Scaramucci found himself fending off pointed questions from Gasparino and Gary Kaminsky about Trump's approach to trade agreements. Scaramucci told Gasparino that when Chinese get wealthier, "they don't" buy more American products.

Scaramucci on that episode made an argument Trump is certain to make himself: "The Democrats seem to coalesce about- around somebody that they may not necessarily like, but the Republicans are having a very hard time doing it," Scaramucci said.

Great moments in business television: Carl Icahn’s tip for poker/life

Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week" has transitioned from independent production to Fox Business regular.

One early episode of the new franchise in May 2015 (see below) resonates perhaps like few other interviews on business television.

Carl Icahn explained how he was a cabana boy at the Malibu Beach Club in need of $750 for room and board at Princeton.

He said he was invited to a poker game at the club and got cleaned out and made a momentous decision:

Learn how to play poker.

So, "I read 3 books on poker," Icahn said. And this is the money quote: "These guys never read a book on it in their lives. And it's all mathematics, it really is."

"At the end of the summer, I had 2 grand. 2,000. And that's when room and board was only 750," he said, adding he had $10,000 saved after 4 years of college.

So much to infer from this brief recollection. One is that most people, even smart people, even at work, are rarely trying to improve. (Mostly they want to be more greatly appreciated for the work they've already done.) Surely you know someone who has attempted to write a book; did that person first read a book about how to write a book? Does the person who cuts your hair regularly ask people to allow him/her to practice with free cuts or ask other stylists to evaluate his/her performance?

Another inference is that many of those people, even smart people, are sitting ducks for an upstart who simply applies effort to the competitive process.

Third is the value of pressing an advantage. Likely the most difficult element of Carl’s story is achieving the invitation to the poker game. Most people making such an achievement would consider it mission accomplished: "Now that I'm playing poker with these guys, one of them will hire me or set me up on Wall Street."

Carl realized an even better outcome: Not only play poker with them, but win.

Free advice. Worth a fortune.

Bass: Emerging markets only in the 5th inning

Airing bonus clips from earlier episodes, "Wall Street Week" gave viewers a few more soundbites from Kyle Bass and Ricky Sandler.

Bass had the most compelling commentary, stating emerging markets are only in the mid-5th inning or early 6th inning of their meltdown. (What he didn't mention is that it's not a 3-3 game, but more like a 3-13 game.)

Bass also predicted "macro forces" would somehow "overcome" whatever happens in the U.S. elections; he likened the Republican race to "Hollywood." (Actually this election is a disaster for the stock market; wait'll you hear the stuff that's making headlines in April, June, August.)

Bass said he's positioned for a "pretty material devaluation" in the yuan in 12-18 months.

Are the markets pricing in the possibility of a Bernie-Donald duel?

Markets are getting shellacked in January, and oil is rightly bearing much of the blame.

There's another scary prospect. You're not going to hear it on "Wall Street Week" or even on CNBC because these programs are in competition to land prominent politicians (note the "WSW" appearance of Jeb Bush, below).

Maybe the financial markets are concerned about any of the presidential candidates actually winning and have no confidence in any of them.

Jeb was asked for policy views. He wasn't asked what his bomb (so far) of a candidacy has done to the financial markets.

The Republican field is a disaster. There's no telling how dysfunctional a Trump or Cruz administration would be. Marco Rubio, sensational at rattling off a world view and a mechanic's knowledge of government, doesn't seem ready for the job and ignites nothing on the stump; the answer to "should this person be president" isn't a convincing one.

The markets might settle for Hillary ... except she can't win. Democrats miss her husband. They aren't excited. The ones who are are voting for Bernie Sanders. Clinton might lose Iowa and New Hampshire in 2016. The narrative is that those losses won't count; she'll take over in the diverse states, as if Sanders momentum would come grinding to a halt.

She once had all the 2008 superdelegates too.

If she loses Iowa, how does the speech go? "I see real momentum in this campaign, real excitement at our rallies for all the aid we're going to provide the middle class ..."

At this point, the markets would love to see Mitt Romney vs. Jerry Brown. Romney could still easily lay claim to the considerable anti-Trump coalition. Gov. Moonbeam, though, doesn't seem prepared for a late entry. That leaves John Kerry or even Gore, but the presence of each figures to only dilute Hillary and make Sanders stronger. Joe Biden wouldn't be taken seriously by changing his mind.

It's not at all out of the question that we'll see Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders fielding questions from Jim Lehrer next fall. Such a scenario — 5%, 10%, 75%, whatever — should at least be in strategists' models.

Given that, it was rather startling to hear Jon Hirtle declare on the Jan. 17, 2016, edition of "Wall Street Week" that "I don't think it matters" who wins, predicting the U.S. is able to "power through this no matter who's getting elected."

Rob Sechan did offer that Hillary Clinton's tweet about drug prices suggests the markets will be affected by this race. But that's what everyone says; it's the only one they know. Nobody ever suggests what industries are losers under a Trump, Cruz or Sanders administration.

In another startling comment, Hirtle actually said he likes emerging markets better than developed markets. He said "the real risk" to the U.S. economy is a "bubble in the equity market."

"There's no signs of an overheated market right now," Hirtle said.

Sechan said he's "constructive" on risk assets but that the markets are at an "inflection point" as the Fed pushes higher rates.

Sechan said there's a possibility that global turmoil "spills over into the real economy" in terms of confidence and lending.

That seems an understatement; admittedly the show was taped before the debacle (and recovery) of the week ending Jan. 22.

John Thiel, the star guest of the bulk of the program, disagreed with Hirtle and Sechan, stating, "We're a little bit concerned about emerging markets."

Thiel did call the U.S. economy "solid." He made a curious comment about the role of Merrill Lynch wealth management: "Our job is to help deliver you the returns of- that financial markets provide," he said, which sounds equivalent to "index fund."

Thiel also said that taking a Dale Carnegie course helped him "unbelievably well" and let him "accept people for who they were."

Doubling your money,

simply by spending it

Barbara Corcoran was the star guest of the latest "Wall Street Week," and Corcoran is very smart and very good on television and well-versed in sound bites, but it was the commentary from Henry Cisneros that raised eyebrows.

Cisneros, a Democrat, was asked about government's role in the housing sector and said this: "Fundamentally the role of government is to make sure we create the conditions in which people can live in decent housing."

"Create the conditions" ...

Many would argue that Cisneros' view is the same kind of mentality that led to both urban blight and the 2008 financial crisis.

One would like to ask Cisneros if the government should assist people who otherwise can't qualify for a mortgage in achieving home ownership.

If a guy isn't ready for the NBA but you install him on the Celtics roster, it might be a visionary move ... or it might not.

Cisneros is an agreeable, well-liked government figure, which is why he has achieved high levels in the real-estate industry and why his troubles were swept away by party leaders.

He said home ownership remains an American dream and that the U.S. is experiencing a "moment of urban renaissance ... all over the country."

"USC's the biggest employer in Los Angeles," Cisneros said, which if true should give people pause about the tentacles of higher education.

Gary Kaminsky challenged Cisneros on this renaissance, suggesting it doesn't sound good for suburbia of Middle America.

Cisneros responded, "There'll always be a population that a- for that phase in life wants to be in the suburbs," and then claimed that "immigrants" are "filling in in, in suburban places."

Cisneros should've drawn groans in closing, citing old municipal water systems and saying his new focus is "urban infrastructure," which is another way of getting on the gravy train of government spending (at least he didn't call it an "investment").

Corcoran, remarkably eloquent, has mastered television on "Shark Tank" and quite candidly described succeeding at real estate through setbacks and determination.

A boyfriend-partner "just happened to fall in love with my secretary," Corcoran revealed, adding "I was angry" and "fueled by my fury for years."

Corcoran indicated, as smart and successful people have a knack for doing, that risk-taking generally pans out.

"I think money is meant to be spent," she said. "In throwing it out, it's always come back to me doublefold."

Like so many female entrepreneurs on CNBC, Corcoran lamented a lack of assertion from her gender.

"Men claim territory. Women don't do it," she said.

Rising interest rates were briefly addressed on the program. "Short term, it's a boost to the housing market," Corcoran said.

Unfortunately, neither Corcoran nor Cisneros were asked about educational background, which has dwindled as a show staple.

Corcoran had fairly nice words for Donald Trump. "He totally changed people's attitude" about luxury living in Manhattan, she said.

Thankfully Corcoran wasn't scheduled on the same episode as Jeb Bush. In a stark condemnation of not just Trump, Corcoran said that when George Bush (sic not clear which one, presumably latter) was running the 2nd time, she bought a home in Canada just in case and held it throughout his term. She doesn't know which country she'll rely on this time in case of a Trump victory, "just in case I need to make a fast exit."

‘Rates will not normalize in our lifetime’

This time, the next crisis took a back seat.

Kyle Bass, who is often predicting the next disaster either in CNBC appearances or on the speaking circuit, sat down with the "Wall Street Week" duo and freely spoke about his background as much as his research project du jour.

It was Bass' best TV appearance.

Bass, who once worked at Bear Stearns, explained that in July 2006, he began to notice statistics indicating rising mortgage defaults and launched a short vehicle on Sept. 16-17 simply because he was concerned that if he waited until Oct. 1, others would see the late September data and beat him to the trade.

"I couldn't wait for another data point," he said.

Gary Kaminsky asked an excellent question as to how the banks were able to keep selling mortgage-backed securities as people such as Bass were spotting a negative trend. Bass didn't really answer but did say that they could no longer sell these securities by June 2007.

He revealed that he presented his theory to the Fed. The Fed, says Bass, merely told him that home prices track incomes, and because incomes were OK, the central bank didn't see a crisis.

Bass defended his role in profiting from the housing debacle, stating he wasn't a cause but an observer in the way that people play fantasy football.

It is not an entirely uncommon theory, but Bass asserted, "Rates will not normalize in our lifetime."

He said if not for the Fed's backstop, Goldman Sachs would only exist as part of another company. (Who knows, maybe Berkshire Hathaway.)

Anthony Scaramucci also paused the proceedings several times to explain some of Bass' terminology. Bass also patiently explained why he is targeting drug patents and the resistance he has received. Bass and Kaminsky agreed that pharmaceutical ads are on TV all the time, prompting Scaramucci to crack that Kaminsky's favorite ad "has nothing to do with cholesterol."

Bass said his "dogmatic" view of constrained energy supplies has hurt him this year, but he still sees "massive opportunity in energy" if you buy within 6 months and can wait 3-5 years.

Jeb’s dinner party (a/k/a why he’s struggling to gain traction in the presidential race)

It happened so late in the broadcast, we nearly overlooked it.

But Jeb Bush's chat on "Wall Street Week" included an answer for a presidential politician that is best described as "lame."

Gary Kaminsky asked Bush, "If you could have dinner later tonight with any 3 people, dead or alive, who would it be."

This is one of those common, fair, mildly interesting political queries that gets a little bit outside the box of policy talking points.

There are a few obvious, feel-good answers.

Jeb Bush responded this way: "I'll tell you 2 of 'em, uh, that I try to have dinner with regularly, it's George Shultz, and Henry Kissinger. 2 of the greatest minds, even though they're over 90. Greatest, greatest strategic thinkers."

Seriously?

Out of ALL the human beings who have EVER lived, these are the people Jeb Bush would choose to have dinner with tonight?? A couple secretaries of state?? Rather than Reagan???

Does this fellow need some curiosity steroids, or what?

Think of the possibilities. Washington and Lincoln, of course. Shakespeare. Einstein. King. Da Vinci. Pope John Paul II. Edison. Grant. Mozart. Lindbergh. JFK. Bogart. Jackie Robinson. Neil Armstrong. Hitchcock. Ben Franklin. Homer. John Lennon. Kate Upton. Charlie Sheen.

A fine Republican answer would be something to the effect of, "Lincoln, Mother Teresa, and Steve Jobs." It shows reverence for history, compassion, and tech curiosity. None can fire back at you in the press.

This fellow can only cite longtime party insiders who were never elected to any office?

People who are associated with his father's era?

Could any statement possibly suggest "out of touch" as much as this one?

Could this person be just the ticket for GOP?

Way, way back in U.S. history, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams sailed to France with the same message.

The French loved Franklin and had little use for Adams.

That's politics.

Presidential elections are decades if not lifetimes in the making and aren't determined by strategies or policies or ideologies.

Donald Trump rattles it off at a podium like nobody's business. He's funny. He's also polarizing. Some think he's a joke.

Jeb Bush is never going to rattle it off at a podium like that, and he's never going to be funny.

That's become abundantly clear in the fascinating Republican primary race and in Bush's interview on Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week," the first 2016 presidential candidate to appear on the program.

Mostly, Bush made clear what is the biggest problem for anyone running for president: There's nothing to do.

Co-host Gary Kaminsky asked Bush why he is running. Bush offered 2 reasons: "Protect the homeland" and the belief that "we have to lead the world."

Scaramucci asked Bush what he would tell Scaramucci's mother, who's watching the show, about making the country safer. Bush's answer was semantical, stating he will call the problem "Islamic radical terrorism."

Scaramucci said, "So we're gonna end the political correctness of that."

Bush said his goal is "to fight it over there rather than here," which sounds OK except for those who weren't sold on the Iraq invasion and heard George W. Bush say the same thing.

Bush said we need to "include a metadata program" under the Patriot Act for detecting the bad guys. (He added that "there's no evidence, none whatsoever" that the government is spying on American citizens).

Bush hardly made any kind of case against Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton. There was no mention of tax rates or fiscal issues or Federal Reserve policy. He only briefly alluded to Clinton after Kaminsky suggested a "double standard" in how the media gives Clinton a pass for making money while she criticizes Wall Street.

Calling for a repeal of Dodd-Frank, Bush said there's "perhaps greater systemic risk today because there's more concentration of assets."

He credited Hank Paulson for creating the model of "full engagement" and "constant communication" that the Chinese don't have.

Gary Kaminsky asked an intriguing question, whether China is a friend or enemy. Clearly sensitive to Trump's appeal, Bush asserted, "China is our adversary ... I don't view them as an ally or a friend." (Obviously, he doesn't take much stock of "The Martian.")

Anthony Scaramucci, who noted he is on Bush's national finance committee, said the show is impartial and that they have reached out to other candidates and "hope to get some of them on the show too."

Bush initially said some candidates are having "nonserious kinda conversations" and later declared Donald Trump is "not qualified to be president ... he's not a serious candidate."

Scaramucci said Bush has a "presidential personality" and "very low key approach" but then made the assertion that "people are looking for something a little more bombastic," at least in the short term.

Bush declared, "Politics is a mirror image of our culture" and added, "People want hope."

That's missing the point. People want whatever they like.

If Ronald Reagan were running today, he'd be leading a small field with 30-plus percent, and pundits would be talking about how the country is embracing conservatism and optimism. If Bill Clinton were running, they'd be talking about how the country wants youth and a fresh start. (Just wait'll you see those headlines at the 2016 Democratic convention when the pundits declare, "Bill's speech sealed it for Hillary!")

The size of the Republican presidential field indicates a serious problem. Some people will run for president regardless of their prospects. Most, though, make careful assessments of the field. The 2 most important assessments were made by Donald Trump and Marco Rubio. Had Bush been invincible, the former, who wouldn't take on Barack Obama, wouldn't have bothered, and the latter would've waited for 2020 or 2024.

To this point, Bush has not been as good of a candidate as Mitt Romney.

Nevertheless, Bush, incredibly, remains capable of winning the nomination. Until they start voting, no one is really sure whether Trump's support is less than a mile wide or more than an inch deep.

The mainstream opening has been there for Rubio. For whatever reason, he hasn't seized it and presumably can't.

Eventually, Republican voters who dislike Trump are going to have to rally around someone. Bush, at this stage, is as likely a choice as anyone else.

Here's the wild card.

Bush is an extraordinarily desirable VP candidate. Enormous demographic reach and political heft. If he does not win the nomination, the person who does will be ringing Bush's phone every 5 minutes.

Would he do it for Donald Trump, Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz? The guess here is probably not. Chris Christie or John Kasich? Maybe. Probably depends on the magnitude of Bush's defeat if he were not to win the nomination.

Hillary Clinton has no such easy choice and might well have to ask Joe Biden to stick around.

Hang in there, Jeb.

What’s the goal, Ben?

One of the curiosities about the Federal Reserve is that the "dual mandate" is often discussed ... but the "goal" never is.

Permanent full employment? Rock-steady 2.0% inflation? Or some variations?

We'd certainly like to ask that question of former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke.

Extended clips of Bernanke's "Wall Street Week" interview aired last weekend in a "Part 2" follow-up. It included a good question from co-host Gary Kaminsky about the ramifications of people saving more money than usual.

"Normally I think savings is a good thing," Bernanke said, "but only if you have a full-employment economy."

Of course, often we don't have a full-employment economy.

Even now, skeptics say the only reason unemployment is so low is because many have dropped out of the work force.

Bernanke's comment is strange. Savings is always good. If you are not saving some portion of your money, you are making a mistake. Everyone should live within his or her means. Do what you can to extend your means, create additional income.

Bernanke is referring to broad statistics in which too much money is hoarded and not spent on goods and services. Indeed, that is troubling for an economy.

There remains an elusive issue: What is the best economy? This should not be difficult to answer. For example, what is the Yankees' goal? Win 115 games, then the World Series. Some might say it would be better to win, say, 95 games, have some drama, but still win the World Series.

For the Federal Reserve, a massive bureaucratic consensus, the answer isn't so easy. It has to deal with cross-currents of goals.

But it still has to make decisions.

And Mr. Bernanke should be able to define what the goal is.

Presumably, based strictly on observation, the Federal Reserve's goal is to avoid any kind of catastrophe. It plays defense, not offense. It reacts. It's a secondary, not a receiving corps. It doesn't want to create a boom, but limit the downside. It is like a doctor. You go to see it when feeling ill; you don't pay a visit when you're simply trying to improve your bench press.

If the Fed had its way, Charles Lindbergh would've flown to Nova Scotia, then Iceland, then London, then Paris.

But human beings wanted Lindbergh — and the other brave souls who tried it — to fly from New York to Paris, no stops.

The opinion here is that human beings need regular order. With an occasional disruption.

A human being who wakes up the same time every day and eats the same food every day and does the same thing every day and gets paid the same every day will quickly become bored, stagnant. (We're talking Soviet bloc here.)

A human being who wakes up at different times and makes different amounts of money every day might do something dynamic but is also not ideal. He or she does not have enough structure in his or her life to progress.

Extrapolating these concepts to the Federal Reserve, it seems the goal is more the former than the latter.

The Fed would likely prefer that stocks rise year after year at a 5% clip.

But the truth is, to get ahead, to advance, the boundaries need to be pushed.

And so the gains in tech stocks from 1995-1999 and the gains in mortgage bonds up till about 2006, in at least one way of thinking, were all good — even taking account of the aftermath from 2000-2002 and 2008-2009. They represented a certain euphoria needed once by every generation or so. Perhaps the gains outweigh the pain. And the whole debacle should be hailed as a victory.

Would Ben Bernanke say that Lehman Brothers' demise was a good thing? Probably not. He is a highly conditioned bureaucrat, which means, status quo, status quo.

But status quo doesn't advance civilization, and maybe Lehman's demise was a good thing. Lehman pushed the envelope for extreme returns. So did many others. Lehman happened to get burned because, for whatever reasons that are beyond the grasp of this page, it wasn't as well-equipped as the others. It jumped into a bubble and apparently had the least protection.

Many good people suffered the consequences. Good people find a way to get back on their feet.

Ben S. Bernanke, given his status, cannot say exactly what he thinks.

This page can.

One wonders if Mr. Bernanke thinks human beings should have a permanent safety net ... or whether they need to cut the cord to advance humankind.

Whether someone waiting for a boat in Göteborg in the 1800s should be saying, "I'm going to make my family Americans no matter what," or, "If it doesn't work out, I'll just come back."

Here's to the pioneers, those who took a risk for the possibility of something better.

To the defense of millennials

The latest episode of "Wall Street Week" didn't have a Treasury secretary, Fed chief or hedge fund legend, but it did have a snappy, spirited discussion from a capable panel.

The most eye-opening comment came from host Anthony Scaramucci, who asserted, "We'll probably get tax reform," something this page highly doubts. There is absolutely no unifying figure in the 2016 race, and we'll be back to the fiscal cliff/shutdown scenarios (as if we ever got past them).

JJ Kinahan said there's a "great chance" for a rally at the beginning of 2016. Co-host Gary Kaminsky predicted "the longer end of the curve is going to go down."

Kaminsky credited James Bernstein with calling a 1,000-point drop in the Dow on Aug. 17. Bernstein said there were "mathematical indications" in the prior 7 months that selling was taking over.

Keith Banks, the featured guest and like Kinahan, a fine regular on CNBC, explained that US Trust is the wealth management arm of Bank of America and has a $3 million minimum.

Banks likes financials and energy, the latter with only a longer-term horizon.

Banks doesn't like utilities or telecom. He said he wants to own bonds at the short end and long end of the curve.

Bernstein likes TR, MO, ADM and CPB. He said it's "shocking" to think someone who has never held elective office could be elected president.

Banks said millennials have "pent-up" housing demand. Bernstein didn't seem to think millennials have much in the way of income. Kinahan said it bugs him to hear people scoff at the millennial generation, stating they work hard and are looking to get ahead just like previous generations.

Trump has ghostwriters

The latest installment of "Wall Street Week," sans host Anthony Scaramucci, explored exactly how someone makes a magazine's top 100 list. (Our favorite is the "30 under 30" megahot journalists list.)

Co-host Gary Kaminsky brought in Richard Bradley of Worth, who discussed how the mag's most powerful people in global finance included John Oliver but not Don Trump.

Apparently impressed by Oliver's take on net neutrality, Bradley suggested Oliver is one of the most powerful people in global finance because of the "ability to change people's minds; the ability to reach an audience."

Bradley said Trump didn't make the list because prior to running for president, it wasn't like he was writing serious economic proposals in NYT op-eds, and nowadays he "probably has braintrusts writing that stuff for him."

"Braintrusts?"

Most of the program was actually devoted to Larry Altman and Ben Thompson, featuring spirited discussion on the state of the markets intermingled with flat assessments of the muni-bond space.

In the most provocative commentary, Altman stated, "We may never have 2% unemployment- uh, 2% inflation again," arguing that "they should be raising rates to normalize things so people can make judgments and we can have a consistency in policy."

This first part is definitely true, or possible, that 2% inflation may just not be reality ... but we can't figure out why hiking rates to create a different "normal" makes more sense than just accepting the actual "normal."

Thompson suggested one of the strangest arguments in financial media, that the Fed should raise rates so that it will be able to lower them again during the next slowdown, which is like driving your car 10 mph under the speed limit so that if you're pressed for time, you can speed up to the actual limit.

Thompson said that conservative investors in the muni space can expect 1½%, while those with a broader approach can look for 2%. He also seemed to think a certain Midwestern city's yields present opportunity.

"We're not worried about imminent default in Chicago," Thompson said.

Altman said 2008 was his best year for trading, but today's computers have "overwhelmed" the market.

Is it possible the 2008 financial crisis was a win-win?

The country, and world, are lucky that Ben S. Bernanke was on hand to organize the resolution of the 2008 financial crisis.

That is not to say everything about it was ideal. But whatever was going to happen needed a steady hand, a non-defensive, non-polarizing figure. This fellow is affable and remarkably intelligent and critically lacked what might've been a deal breaker — an ego.

Of course the same resolution would've happened without him. U.S. central bank and Treasury decisions are made through massive levels of consensus and bureaucracy.

Many on Wall Street applaud those Fed actions today; others criticize. Enough have applauded to establish the 2008 financial measures as one of the 2 most important American precedents of this century. (The other being related to 9/11, but that's a whole other topic.)

Based on anecdotal evidence, those harboring hard feelings toward the Fed cite at least 3 reasons, 1) that money shouldn't be this easy at least for this long, 2) that ZIRP benefits Wall Street elites and hurts regular Americans, and 3) the Fed is losing control of the bond market when and if ZIRP triggers runaway inflation.

Bernanke spent several moments on Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week" defending the Fed against Argument 2, stating his goal was to "try to do the right thing for Main Street." That meant, as credit markets were freezing up, stepping in and "backstopping commercial paper" to unfreeze them.

The result has been a curious discovery: "Every loan we made, was paid back with interest, and, we- we turned over lots of profits to the, uh, Treasury, reducing the deficit," Bernanke said.

It's a bit like having someone save you from flunking a test but in exchange forcing you to study a couple of hours a night.

Bernanke was not asked what would've happened if there had been no TARP (a Treasury program) or emergency Fed measures. Nor was he asked about the significance of a precedent. We now know that any institution whose failure would be in the ballpark of Lehman Brothers will not actually fail. But there is a steep price. The Fed and Treasury will supply cash to more than just the most beleaguered entity, and the money will be repaid to taxpayers with interest under stringent regulation.

The Lehman "ballpark" is a gray area. MF Global was not in it. General Motors was. The standard is pretty high.

Somehow, taxpayers seem to have come out ahead. It may be, to the disdain of the most strident free-marketers, that TARP and open discount windows are a revelation along the lines of Social Security or Medicare. Possibly, troubled companies are made better and jobs are saved and fiscally America is made healthier by what amounts to a special corporate income tax.

Bernanke was not asked about hypotheticals, but there are many good ones. Chief among them being the importance of the stock market in what the Fed and government do.

If the dot-com bubble had occurred after the 2008 financial crisis, it seems unlikely there would be TARP. The financial system would not freeze to death if Pets.com went under. Pumping billions into Exodus Communications and America Online would've provided a floor under those stocks but very little assurance that the money would ever be paid back.

Yet, the dot-com crash did as much damage to Americans' 401(k)s as the 2008 crisis. And we saw how the stock market influenced the 2008 TARP vote. Many were against it, until they saw the Dow falling 700 points in a day.

So it's fair to ask Mr. Bernanke if the stock market is the tail wagging the Fed's dog.

He only gave token lip service to a decent question on too big to fail, calling it "still a concern" but saying we're "making a lot of progress" on that subject somehow.

Besides stating "I don't get this, uh, inequality thing," he addressed the other complaints about ZIRP. He said if rates weren't around zero, we would've kept a recession intact; "the argument is a strange one."

In what may prove his most controversial line of the program, he told Gary Kaminsky, "Well, we knew from the beginning that there was no risk of inflation. The reason there's no risk of inflation is that the Fed is able to tighten monetary policy at the appropriate time, it's able to raise interest rates at the appropriate time, and will. And, the markets completely believe that. ... There just is no credibility to the idea that inflation's gonna get out of control."

He is correct that markets believe that. But not everyone likes it.

Promoting his book, which happened on this program, Bernanke's most prominent headline has been his apparent dissatisfaction over punishment for the 2008 crisis, the fact institutions were heavily fined but indidviduals essentially have not been held responsible.

"My problem is with the prosecution strategy," he said, without explaining here or in other appearances which humans should be jailed.

He said housing prices peaked in 2006 and that it's "about right" to say the financial crisis began with the collapse of the Bear Stearns hedge funds in 2007.

Gary Kaminsky said banks were running out of cash on the Friday before Lehman's collapse. Bernanke stated, "We know now that the recession began in December of 2007," although anyone with a hint of skepticism knows that "recession" means different things to different people and shouldn't be solely the domain of elite academics.

The former Fed chief humbly explained how his family were the town pharmacists in Dillon, South Carolina. According to his Wikipedia page, he scored a 1,590 out of 1,600 on the SAT, making him eligible for Harvard.

In a curious understatement, he said, "It's a place where you could, uh, learn about practically anything." Educational background is an impressive feature of this program, but here again, it is left to the imagination whether Harvard is a cause or effect of Ben S. Bernanke's brilliance.

Bernanke said he paid for college by being a construction worker and then working at the Dillon tourist attraction South of the Border, at the "midpoint" between New York and Miami.

He played ping-pong with his future wife on a blind date and doesn't remember who won, but he thinks they saw a Fellini movie afterwards.

Scaramucci asked about advice for a future Fed chair, but Bernanke had little to say, advising those in that position to look at the financial system "as a whole" and not piecemeal, and be wary of problems beneath the surface.

Bernanke said he was a "registered Republican" but dubiously hasn't voted since being Fed chief. If any reason is a good reason for forsaking the right to vote, we have yet to hear it.

He shrugged off the notion of certain presidential candidates that the fix is in between the Fed and the Democratic Party. There is "literally no discussion whatsoever of elections, of politics, of campaigns" in the FOMC meetings, Bernanke said.

When advertising is better

targeted, we’re all winners

Lawrence Summers is undoubtedly brilliant, influential and even controversial.

Add "tragic" to that list.

By his chosen career path, which has brought him prominence, wealth and stature, Summers has put his wonderful mind in a straitjacket.

He is hardly free to say what he really thinks. He let his guard down at least once, as Harvard president. In terms of expanding people's minds, he can't be considered an overachiever. It's like limiting Willie Mays to pinch-running.

Co-host Gary Kaminsky declares before Summers' appearance on Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week" that "Larry Summers is one of the most influential thinkers of our time." But it seems much of that influence is devoted to scoring points in the Clintons' decades-old political apparatus. He must have thousands of wonderful things he'd like to say, but every one of them has ramifications in the political media all the way up to the White House.

This person is far more of a reactor than innovator. He is elite damage control. He made a point of declaring on the program that "if you look since the Second World War, not a single recession was predicted by the Fed, by the IMF, or by the consensus of professional economists."

Exactly. He's not out there to invent economies that avoid recessions or currency debacles; he opines on what to do after they happen.

Summers' appearance was likely the best of Scaramucci's program to date, although it requires some inferences.

Summers was not asked, for example, what a utopian economy is. Would it be a permanent GDP number and inflation number and jobless number, and would it include other metrics that would presumably merit increased government intervention to maintain? Or would it be more of a dynamic, boom-bust environment that more quickly weeds out laggards and rewards winners and requires less of a hand of government?

Or is it simply one, as Summers unfortunately hinted, run by a certain party indefinitely?

The best question of the program came late from Kaminsky, who asked about social media's impact on the economy.

"I think things that bring people together are presumptively good," Summers said. "So I think these things are positive socially. I think these things are positive economically. They let people, uh, target, uh, advertising. They let people target, uh, products, uh, in a better way than they otherwise could."

That answer, while giving him a slight pause, sounded like one Summers has given before. But he seemed less prepared for Kaminsky's follow-up about the view that social media hurts the economy even while "saving people money" by putting some people out of work.

"I don't think they're shrinking the economy," Summers said, calling Facebook a force for good. "I think it's a broad social and economic positive."

Of course. Silicon Valley is a big player in the nation's political infrastructure, so even one of the nation's foremost academics can't even suggest a downside, not even the amount of time people are spending posting vacation photos as opposed to doing something more productive.

This exchange actually came after Scaramucci pointed out that Summers was on the MIT debate team, which Summers said taught him there are "2 perspectives on anything." Except the downside of social media, apparently.

One wonders if Summers would relish debate on a few of his other statements. Summers opined, "The United States can't be an oasis of prosperity in a world that is systematically troubled." What exactly does that mean, we're only as good as Greece or Venezuela? (Translation: Trade agreements backed by Democratic presidents are necessary.)

Summers defined infrastructure spending as an "investment." This is a common Democratic Party platform. But building and maintaining a road takes more and more money over time, as opposed to buying Under Armour stock and hoping to sell it later for a higher price. Roads and airports don't hand us cash.

Explaining that "I would embark upon a 10-year, trillion-dollar program of infrastructure investment which would initally be financed by borrowing" (and later by gasoline and carbon taxes if the economy overheats (snicker)), Summers suggested people look at JFK Airport and "look at 30,000 schools where the paint is chipping off, uh, the walls."

Seriously? Lawrence Summers claims to have noticed paint chipping off the walls at 30,000 schools, and isn't impressed by JFK or LaGuardia airports ... and believes $1 trillion over 10 years is needed to fix it?

This country should be giving congressmen $1 trillion to dispense to local builders because Lawrence Summers noticed crummy buildings or roads at LaGuardia?

Scaramucci painted Summers as a centrist, telling him that associates will say that the way Summers thinks, "It's really not about left or right ... it's more about right or wrong," yet in the political circles in which Summers operates, there are definitely at least 2 perspectives on right and wrong.

Scaramucci suggested such a project might be "good debt."

Summers also claimed that all the car repairs caused by "excessive potholes" would amount to a 40-cent-a-gallon gasoline tax and called it "crazy" that we're spending the lowest percentage of our income since World War II on infrastructure. (Wonder how that will go over in the South, which doesn't have winter weather concerns on its roads and therefore should get a lower percentage of the $1 trillion.)

Summers said on the program that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt "caused us to win World War, uh, II." One person, in the 3rd term of a presidency and in rapidly declining health, "caused" the United States to win World War II?

An important dialogue took place over interest rates. Kaminsky told Summers, "The Fed listened to you" about not lowering rates. Summers shrugged at that but asserted the economy is "healthier" because the Fed didn't hike.

Then he got to the money quote: "I don't know why, what the strong case would be, uh, for raising rates," Summers said.

Exactly. There's no inflation. There's no reason to rise, except that a lot of people on television are offended by ZIRP, perhaps rightly so, and just don't want it and haven't wanted it since 2009.

Summers said Q3 growth might be 1½% and that "growth in the United States isn't so far above stall speed."

He said Donald Trump's comments about Fed collusion with the White House "nonsense."

Summers told Scaramucci and Kaminsky he came from suburban Philadelphia and attended public schools; his parents were both economists.

His parents were "very liberal." He said he's "not sure" that he had role models, but FDR "was a kind of hero for me," and he would mention him 3 times in the program.

He said he grew up an Eagles and Phillies fans, but that has morphed into Boston allegiances.

Summers said he was in the "chess club and the math club" and that the MIT debate team taught him to number his arguments; "ever since, people make fun of me" for enumerating his points.

He said "the way you become a Harvard professor or a professor at a great university is that there's some conventional wisdom in your field, and you overturn it," adding that once a person reaches that stature, it "tends to be hard to get them to sort of work together or move forward."

Interesting. Our smartest people are operating in silos.

Summers said that as a teacher, his goal is not to be the "easiest one," and he likes hearing students say he prompted them to think about things in a different way.

Summers said he'd rather play the U.S. "hand" in the global economy than anyone else's. But he thinks we have "real challenges," which is basically the Hillary platform.

He said if he could have dinner with 3 people it would be FDR, Churchill and Einstein.

Adopting a favorite cliche of people seeing old clips of themselves on business television, Summers said, "I sure looked a lot younger" in his 1992 Louis Rukeyser interview, but added a twist, that he thinks he has fewer pounds now.

Summers has clearly thought about signature quotes. He told Scaramucci that he would summarize his legacy as: "He thought hard to make actions better."

And, he believes, "There are no final victories in life, and there are no final defeats."

Helpful advice for

Point72 job-seekers

If we heard correctly, outsiders have about a 1-in-500 chance of becoming a portfolio manager at Point72.

So, might want to ship your resume elsewhere.

Doug Haynes, star guest of the latest installment of Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week," told Gary Kaminsky that "Point72 is sort of descended from SAC, but it's not SAC in any way." (Note the graphic above; "Wall Street Week" somehow still is having problems with spell-check.)

If you want to get to Point72, try a different department. "We hired about 100 analysts last year," Haynes said, adding that the firm has a lot of strong internal candidates for portfolio manager jobs.

Haynes said that in the last couple of years he has looked at 400-500 outside portfolio managers, but in the last round of hiring 9, only 1 was an outsider.

Haynes did nothing to hurt the cause, but he surely could've made a better sales pitch for all the potential analysts who might be watching. He did tell Kaminsky (Scaramucci was off) that turnover for portfolio managers is "well under 10" percent while it's 20% for the industry, and analyst attrition is 5%.

As would be expected, Stevie Cohen doesn't hand over the keys to the kingdom to just anybody. "We knew each other personally pretty well" before Haynes got the post, Haynes said.

Haynes said the temperature on the Point72 trading floor is "in the 60s."

Curiously, Haynes opined at one point that "this is an industry that 10 or 15 years ago had very little barriers to entry; there are a lot now."

Haynes was joined by Michael Cahill and stunning Holly Newman Kroft.

Cahill offered, "We're pretty worried about the general economy," stating export data looks to be down in 2015, something that tends not to happen unless we're in a recession.

Kroft pronounced volatility great for stock pickers and said, as many on the program have said, that now's the time for active management.

Haynes said the consumer side of the economy looks better than the manufacturing side. Stating the Fed has become an "echo chamber," he said he likes health care and retail as well as solar.

Kroft likes midstream MPLs, the pipeline companies, and sees a risk-on market.

Cahill told Kaminsky he disagrees with the view that 90-100% of the market moves are tied to the Fed. Cahill pointed to the China summer. He also touted CF, because of increased production capacity coupled with buybacks.

"Wall Street Week" tends to be chummy. Nevertheless, Kaminsky and Scaramucci, veterans of CNBC though not under that umbrella now, would've been ideal questioners at CNBC's presidential debate. It looks like they won't get a chance for the Nov. 10 Fox Business edition.

Either the Dow is going up,

or it’s going down

Rarely dabbling in timely market calls, "Wall Street Week" came up empty in that department when star guest Elliot Weissbluth turned up in Episode 25.

Weissbluth said he doesn't want to give host Anthony Scaramucci a "glib answer" as to whether the market is a buy because he doesn't know the "360 view" of the questioner's family, children, etc.

This page doesn't really know either, but we do know that there are stocks available to buy and sell, and those stocks do not care whether someone's kids are preparing for Harvard or a trip to the casino.

Co-host Gary Kaminsky, who's having trouble getting his questions answered, asked Weissbluth for 5 characteristics of a good financial advisor.

Weissbluth would only provide 2, stating the first is "a genuine passion for their clients," and No. 2, a "keen understanding" that their clients have "strong emotional reactions" to what happens in the market.

Weissbluth agreed with Kaminsky that advisors should eat their own cooking.

Later, Kaminsky asked Shelley Bergman for 3 underpriced elements of the markets. Bergman said commodities and emerging markets.

Bergman said he does like big pharma and that he's just started looking at energy.

Bergman said the last several months have proved "one of the most confusing landscapes for investors."

Amy Butte said we've had an "extended period of volatility, and that's difficult."

Bergman blamed 90-100% of market volatility on Fed uncertainty.

Amy Butte said it would be "bad" for the Fed not to raise rates.

Elliot Weissbluth said he attended Rice because a New Trier counselor convinced him "Houston's warm, and um, the girls are attractive." Anthony Scaramucci dubbed Hightower as the "Mayo Clinic for wealth management."

Premium opportunity lapse: Chance for intriguing insurance discussion fizzles on ‘Wall Street Week’

It's a hugely relevant topic for the folks squarely in the "Wall Street Week" demographic.

But so many, as was stated on the program, "haven't a clue."

Nevertheless, the basics were largely skipped and a potential crisis came from nowhere in what could've been a highly informative assessment of the life insurance business on "Wall Street Week" — a lot of stepping off the mound or out of the batter's box and suddenly some inside baseball.

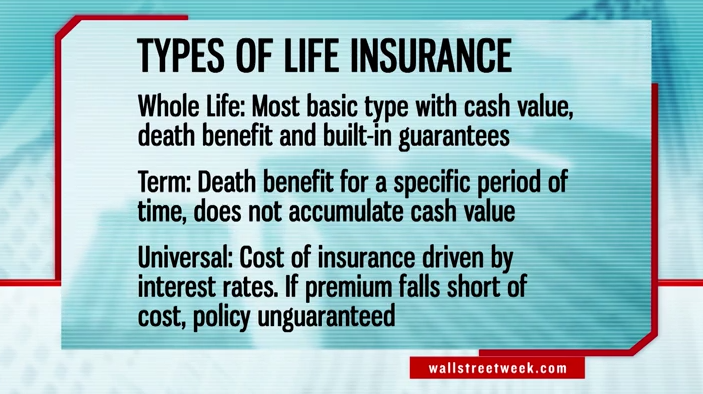

For starters, and we don't mean Jake Arrieta, the chart above, which surfaced around the 20-minute mark, should've been shown at the top of the program and left on the screen throughout.

The star guest was Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Chairman and CEO John Schlifske, who adequately delivered the expected soundbites — albeit with not the greatest salesman's oomph — of the virtues of his company's adviser services and insurance products.

"We're in business, we say, to help people achieve financial security," said Schlifske, adding that it's about solving clients' "vulnerabilities."

Insurance, of course, is safe return over time, compared with equities and bonds; "we believe the markets are like this big casino," said Schlifske.

And then there's the greatest seal of approval: Schlifske said that at 23, while attending grad school at Northwestern after graduating from Carleton, he heard Warren Buffett, who enjoys talking about his stocks in the "big casino," extol the virtues of insurance companies.

Schlifske said young people should know insurance provides "so many uses across your life expectancy."

He described life insurance as "almost like a Swiss Army knife" and said he's never heard anyone lament that they've bought too much life insurance.

But what exactly should people be buying, and how much are these Swiss Army Knives costing them? While universal life was mostly addressed by later guest Henry Montag, term and whole life distinctions were nearly unmentioned.

It wasn't until the latter half of the program that there were hints of storm clouds encroaching on the sunny skies.

"Low interest rates are a headwind for an insurance company," Schlifske conceded, revealing, "We're out about $26 billion of revenue over the last 5 years because of low interest rates."

"I think the best of times are over," Schlifske admitted, adding the market will "tread water."

"I'm not worried that we're in for a Japanese-style recession or depression or anything like that," he said, "but I do think it's hard to see rates going up."

Schlifske, who happened to look up into the set lights on several occasions, pronounced insurance purchases "sort of immune" from the stock market. That prompted a good question from co-host Gary Kaminsky, who asked which economic indicator most correlates with insurance-buying.

Schlifske didn't answer the question, stating only, "We actually have a lot of positive demographics on our side," citing the size of the millennial generation.

But then came TOLI Center East Principal and Certified Financial Planner Henry Montag (below), who leaped way ahead of where the program was in terms of our basic insurance definitions.

Montag referred to EF Hutton bundlng insurance starting in1983 around the time of 14% rates and suggested a looming "crisis" among universal-life policyholders who may not be aware that under today's rates, policies may lapse without additional premiums.

That prompted an exchange in which Schlifske asserted that most people are being informed by their advisors, and "I certainly wouldn't call it a crisis with all due respect," though he conceded "pockets" of trouble.

"Well, with all due respect, I find that many of the sons and daughters haven't a clue," Montag rebutted.

Host Anthony Scaramucci, who said he has "several policies" with Northwestern Mutual, explained (fairly late) that essentially, the lower that rates are, the higher the universal premiums need to be.

Schlifske did assert there are "a number of carriers out there that are making unrealistic assumptions around investment returns in their, uh, universal life, uh, products" and that "somebody's gonna be on the hook."

"If we do stay low for long, those policies are gonna be underwater," Schlifske said.

(Apparent translation of all of the above: If a universal policy lapses, you've been paying for air.)

Montag contended insurance companies fail to reach the masses, that "86% of the population doesn't buy life insurance simply because it's too expensive."

He also raised doubts, as longtime CNBC staple Suze Orman always did, about whole-life policies, suggesting younger people "should perhaps take that money and place it into a lesser-expensive form of insurance" such as term or universal.

But Schlifske likened financial advisors to personal trainers who ring the doorbell in the morning and likened "robo-advising" to having a bunch of Fitbits.

Montag suggested that product innovation in the insurance industry will lean toward the eye-rolling "preponderance of more bundled products" and bring "additional compliance."

An activist investor wonders why people don’t complain about HFT instead

Activist investing, an occasional subject on Anthony Scaramucci's "Wall Street Week," actually found a devil's advocate on the program in Episode 23.

It was James Frischling, whose job description and firm's mission statement weren't well explained (it appears to be a financial-services consultant), who said there's an "immediate cost to the company" when activists start sinking their teeth in.

Frischling was compelled to address arguments from Donald Drapkin, who likened today's activist investing as merely "1 step removed" from the takeover boom of the late '70s and early '80s and said the notion that activist investing doesn't benefit investors is "a lot of nonsense."

"It doesn't mean that every activist is a good guy," Drapkin allowed.

Anthony Scaramucci agreed, "there are some nefarious people out there as well."

Drapkin questioned why people complain about activism when there are high-speed algorithms and "ETF stuff" that are driving share prices wildly up and down without any regard to fundamentals.

Frischling said HFT "accelerates and exacerbates" stock moves.

Frischling curiously said everyone is motivated by his own self-interest. In perhaps the show's funniest moment to date, that prompted Scaramucci to declare that his interest is making co-host Gary Kaminsky "look good," prompting Kaminsky to crack, "Boy, he does it every day."

Drapkin, who has been pushing for a CLF overhaul and succeeded in doing so with the board, called the company a "perfectly well-run, humming machine" that is suffering from the iron ore correction.

Drapkin touted U.S. as the investing destination by citing perma-Armageddonist David Stockman's views on China numbers being unreliable.

In a show with few graphics, the gremlins nevertheless made the most of their opportunity with a botch of "chairman."

Drapkin predicted 18,800 for the Dow year-end, while fellow guest Dick Grasso (who for some reason was on this panel despite having the previous show to himself) said the S&P would be "at or slightly above 2,000." Gary Kaminsky refused a prediction. "Honestly, I don't know," Kaminsky said.

Steve Tananbaum: Some beaten-down media stocks look good

In the latest episode of "Wall Street Week," Rob Sechan offered one theory as to how investors fall behind.

Sechan pointed to "Myopic Risk Aversion," in which people tend to spend too much time mulling their long-term investments and thus become too sensitive to the losses.

Mary Deatherage said her message to anxious clients is "how bad it's not."

In a subject that is always interesting — a person explaining what happened to Bear/Lehman/Wall Street in 2008 — Sechan opined that the salvaging of Bear Stearns "created a general market assumption that every bank out there was too big to fail," but then when Lehman sank, "all hell broke loose."

The star guest of the program, Steve Tananbaum of GoldenTree Asset Management, provided about as many fireworks as the Indianapolis Colts offense, stating the market's August stumble was based on "dissension on what's important to prioritize."

Tananbaum pronounced credit markets "generally very strong" and indicated a reduced recession threat.

Rob Sechan called the current state of the S&P 500 a "bull market correction" caused by "some growth and policy scares." Tananbaum said that is "most likely" the case.

Tananbaum, who said he picked economics at Vassar because it "seemed like a good, social science," did offer a couple of stock picks as the most interesting portion of his discussion, asserting TWX and TRCO are attractive on an overdone media selloff.

Mary Deatherage said August volatility was "like a bungee cord."

Rob Sechan pointed out how the "huge growth story" in energy from 5 years ago is now a "deep value story." Sechan said, as he has on CNBC, that MLPs are attractive.

NYSE panic: scripted

In a full-half-hour "Wall Street Week" session with Dick Grasso that was more tribute than interview, co-host Gary Kaminsky revealed an interesting tactic of the business media.

Kaminsky said that during steep market drops, the "financial channels" would call the NYSE requesting a bunch of people "running around as though there's some sort of panic there."

Well, as anyone who has ever tracked the CNBC.com headlines (many of them dealing with Marc Faber) on DrudgeReport.com knows, fear sells.

Unfortunately, the chat with Grasso could've provided a nice counterweight to whatever point Brad Katsuyama was making months ago (see below, hit PgDn a few times) about how exchanges operate (it's still not clear why the public should care if Katsuyama's computer told him 100,000 shares of IBM are available but only 30,000 of them were in a single block, or how someone gets ahead by cancelling a bunch of orders). But Grasso said legal trading can't be banned and equivocated between helpful HFT (liquidity providers) and non-helpful HFT (algo trend followers).

Co-host Gary Kaminsky asked Grasso if he has made a public statement on Michael Lewis' assertions. Grasso said he hasn't, "but I will now," which was merely that creating any type of advantage for a certain investor that doesn't help the retail or lowest-level investor is a bad move.

Grasso said, in response to a flat "How has the world changed" question from host Anthony Scaramucci, that back in the day, stock exchanges were transparent and obligated to find the best prices for orders. But now, there is a loose collection of transparency, semi-transparency and no transparency, and so the marketplace has been "terribly hurt by a series of initiatives over the years."

Grasso said identifying the "last sale" of a stock such as IBM is impossible, and regulators are "late to the party."

"I think the uptick rule makes no sense today," he added, calling Regulation NMS a "sad, sad experiment."

Grasso's interview appeared to take place the same day as the next episode featuring Steven Tananbaum, and the forthcoming episode including Grasso again with Don Drapkin and James Frischling.

Grasso did say he "loved every day I was there" at the NYSE. He also indicated an alliance of sorts with Gasparino, stating, "I've promised Charlie, somewhat tongue in cheek, that if I were to become mayor, he would become sanitation commissioner."

‘Wall Street Week’ tackles status of Barack Obama at Harvard Law Review

In the latest airing of "Wall Street Week," featuring extended clips of a recent interview with Ken Langone, host Anthony Scaramucci expressed "contrition" for supporting Barack Obama in the 2008 election — a curious situation, given that shortly after, Scaramucci would confront the president in a 2010 CNBC town hall (below) about how Wall Street feels like the White House's "pinata."

On "Wall Street Week," Scaramucci told Langone, "I went to law school with him ... he's a very smart guy, and he graded on/of the Harvard Law Review-"

"He never wrote a piece for the Harvard Law Review," Langone asserted.

"He was the editor of it; he was the president," Scaramucci said.

"How many editors of law reviews never write a piece for that law review? You know, there's a lot about this guy we don't know," Langone said.

Scaramucci explained, "At school, there were 500 kids, he was one of the top 5 that graded on; I have to give him the credit that he's due there. I supported him, and I'm now at St. Peter's Church in confession, saying the act of contrition. And I'm a lifelong Republican, and will remain a lifelong Republican. Just hasn't been the person we all hoped for."

Langone, however, wasn't satisfied. "This guy wouldn't show us his resume. ... Why are there so many things about this man that we don't know about, and he won't share with us?," Langone demanded.

Langone at one point also complained that Obama could've been great had he just been a "1-trick pony" focused on education.

Scaramucci said that Chuck Schumer "tried to push him in that direction, but he wanted to go into health care."

A case for the suits

Hedge funder Ricky Sandler, given the opportunity to make a bull case for KORS on "Wall Street Week," had this to say:

"It has not overextended itself into outlets and sort of damaged the brand," he said.

Perhaps not, but the typical refrain on business television is that the company has saturated certain accessories markets and has simply lost the elite cachet it recently had, something very hard to regain.

Unfortunately the bear case wasn't presented. Sandler said Kors is a "terrific brand" but a "classic example" of today's "market environment," which doesn't really mean anything; it's simply a brand that's not as hot as it was a year ago.

Notably, he has no activist demands or advice to impart at KORS: "We wouldn't have any, um, particular suggestions for them," Sandler said.

Sandler's stint for the entire half hour proved a chipper assessment of a seemingly unrelated array of stocks. However, things curiously got confusing about midway through when Sandler seemed to be arguing for relative outperformance and making absolute money to "buy groceries at the supermarket" at the same time.

He acknowledged that shorts face an uphill battle given the market's average gains over time and said it's been hard to short stocks in this market if you're looking for "absolute money. We believe our job is to generate alpha."

He said his fund is "about 140% long by 95% short."

Explaining his philosophy for Eminence Capital, Sandler said, "growth and value sort of work together" and that his approach is "quality value."

"We own, um, high quality businesses that we think are underpriced in the market for a given reason," he said.

His short targets are companies that figure to disappoint, stocks facing secular pressure and those with accounting issues.

Sandler said he's short RGC, a business that's "inextricably in decline" and presumably in his secular category. Citing movie ticket sales, he asserted, "Kids don't hang out there."

But the movie theater obituary has been written since the dawn of VHS, and every year there are headlines about record openings. Plus, given the steady rise in ticket prices, there appears to be pricing power.

Sandler said "IMAX has some issues as well." His most convincing anti-Regal argument is that the company put itself up for sale last year, and no one offered.

In a new twist on the bond-bubble trade, Sandler pointed to Paris. "You can short French government debt at a cost of 1.3% a year. If this doesn't work out, I lose 1.3% a year. By the way, I hope it doesn't work out," he said.

Unfortunately someone in the graphics department was asleep at the switch while Sandler spoke about Joseph A. Bank (Sandler said "Joseph Banks" (sic) 3 times) and Men's Wearhouse (not "Warehouse"); unfortunately despite the amount of time given to the subject, he never explained why suits are not a value trap as opposed to movie theaters.

Sandler endorsed both EBAY and PYPL, the latter having 20% growth "as far as the eye can see."

Maybe his most controversial call is bullish ZNGA, stating it has gone from 35% mobile to 70% mobile and touting today's gaming environment and feasibility of upgrades.

Sandler, a good guest but prone to too many "ums" on the program, said he studied accounting and finance at the University of Wisconsin but unlike many guests didn't pound the table for higher education. He credited Morris Mark and David Herro for their guidance. He said Aspen is his favorite vacation spot.

5 to 9 — what a way

to make a living

Conversation with Mario Gabelli on "Wall Street Week" proved unfortunately helter-skelter as the famed investor and excellent TV guest was forced to zig and zag among 3 subjects: education, starting his own company and his stock-picking strategy.

A few times, Gabelli touched upon a subject that should come up far more often on the program — what kind of time commitment does it take to be a success in the financial markets.

Gabelli said those who "can work from 5 to 9" will be rewarded.

Unlike Carl Icahn (see below), he did not sweat the particulars of maximizing dollars out of his own shop. "I did not have the confidence that I could gather assets. But I had the confidence I could make money in the market," Gabelli said.

He did not answer host Anthony Scaramucci's question about the age at which he started his firm, merely pointing out how long ago 1977 was.

For strategy, Gabelli explained his formula as seeking to determine what a public company would be worth to a buyer taking it private, conceding that a rival company would be able to pay more for the synergies.

As for the importance of education, Gabelli claimed, "I think basically you go back to what has made America great: it's been the rule of law, it's been a free market with all the warts, and it's been meritocracy, and the underpinning of meritocracy is education."

Actually all of those things including education are not cause of greatness, but effects.

Gabelli said he was a "truant" in 1st grade; "I just walked out of the classrooms a lot."

He spoke in-depth about his global water play and said he likes XYL, BMI, GRC and hydrant-maker MWA. It's unclear what a current catalyst would be; this concept has been mentioned semi-regularly on business television for years if not decades (typically during Jeff Immelt's old Green Week designations that CNBC had to trumpet).

The 2nd half of the program, which featured a Manhattan brightness that felt as though it were taping at dawn, included Yra Harris and Holly Newman Kroft. Harris said he does "top down analyzation (sic)" and finds value in other ways than Gabelli.

Harris said Canada right now presents compelling valuations.

Gold is not an inflation hedge, Harris said, calling stocks rather than gold the "safe haven."

Holly Newman Kroft predicted "inflation is coming" and said she likes "developed Europe," a term she used at least 3 times.

Kroft convincingly told Anthony Scaramucci we'll still have a euro in 5 years, but her similar answer to the 10-year version of that question occurred after a lengthy pause.

Co-host Gary Kaminsky raised an interesting point with Gabelli, stating commodities, energy and industrials suggest a recession in 2015 and wondering if that "sector analysis" will prove accurate.

"I just don't see it," said Gabelli, who said wages and jobs are rising, "debt is tolerable" and housing is on the upswing slowly but steadily.

Gabelli and Harris discussed the extent of politics on Fed decisions but neither mentioned what seems the most intriguing question, whether Yellen will be appointed by whoever the next president is.

"It's very hard to predict China," Kroft said.

Speaking of people's skill sets, Gabelli claimed that when Michael Jordan tried baseball, "They were benching him," but actually he played AA ball for the Chicago White Sox' Birmingham club and led the team in games played with 127.

Fish seems to imply fracking enabled the Iranian deal

With impressive candor, oil-trading legend Mark Fisher on "Wall Street Week" freely admitted his call a few years ago that oil will never sink below $70 was a bust.

He said he's "shocked" that that floor has been shattered and didn't realize companies would be able to produce so much U.S. supply.

Then, he suggested some real-world effects that go beyond the gas pump.

"I don't want to get into politics, but you know, I think a lot of the reason why, with us being energy independent, is a lot of the reason for why we're now going ahead and making the decisions we're making in the Middle East," Fisher said.

The only big decision we're aware of recently is the one involving John Kerry that also is not being called a "treaty" (though it basically is) so that instead of requiring a 2/3 vote, Congress can then pass a resolution against it and then be vetoed by the president in a double-negative with quite possibly barely 33% support to make something happen. (Like Fish said, who wants to get into politics.)

While Fisher is a very unique persona in the financial markets, several things he discussed were right up the "Wall Street Week" formula. Freakishly smart people, unusually hard-working, generally good-looking (though no one's suggesting Fish or Carl Icahn are going to oust Tom Cruise from the "Mission: Impossible" franchise anytime soon), already way ahead by the time most young adults are even thinking about getting ahead.

Fisher was well-prepared for the opening "origin-story" question, volunteering that at age 12 or 13 (the screen text said "12") he noticed a neighbor driving fancy cars. So Fisher knocked on the guy's door and asked what business the guy was in. The guy shut the door on him. Fisher returned and offered the guy a deal: Let Fisher ensure his son graduated from high school in exchange for giving Fisher a job. And that was Fisher's start in the COMEX silver markets.

He didn't mention his college, but the screen text listed Wharton.

Host Anthony Scaramucci asked, given Fisher's early success, "Why'd you go to college?" Fisher said he needed a "back-up plan" because he wasn't actually earning that much money.

Fisher, and later Deepak Narula, seconded a strategy put forward by Marc Lasry a couple of weeks ago, buying assets when someone else is forced to sell.

Scaramucci mentioned Dodd-Frank's impact on the energy space. Fish said energy companies have been forced to hedge to get financing, but banks used to be on the other side of the energy transactions, "and now they're not," so the market recognizes there is a lot of "forced selling."